Even in London, it was clear that nothing would be achievable without greater investment. Reinforcements of fresh, unbattled troops were found and despatched and a new plan hatched. The new strategy involved a landing at Suvla Bay, to cut off the Peninsula in the north. The Munsters, of course would know none of this; they just received the order, at the end of August, to move.

The fresh division, the 10th, were sent first to Mudros. Some of the 29th were resting there. One of the officers of the 10th recorded his impression:

Thus we learned from the men who had been at Gallipoli since they had struggled through the surf and the wire on April 25th the truth as to the nature of the fighting there. They taught us much by their words, but even more by their appearance; for, though fit, they were thin and worn and their eyes carried a weary look that told of the strain they had been through.

The landings at Suvla fell into a familiar pattern, initial success followed by failure, but with a new twist. What was unexpected was that the landings were, in a sense, too easy, against weak Turkish forces. What was then needed was a swift advance to capture the dominating hills beyond the coastal plain. Minds accustomed to the minimal advances of the Western Front could not adjust to this opportunity. Instead of exploiting the situation and advancing rapidly, they dug in against an expected counter-attack, which never came. So the Turks were given time to rush up troops and retain the heights.

The Munsters did not take part in the first weeks of Suvla. They were shipped in on August 21st and launched against Scimitar Hill. Here a new experience of horror awaited them. Shelling had set alight the dry undergrowth and many of the wounded were simply burned alive. Guy Nightingale described this:

We had to lie flat at the bottom of the trench while the flames swept over the top. Luckily both sides didn’t catch simultaneously or I don’t know what might have happened. After the gorse was burnt the smoke nearly asphyxiated us! … The whole attack was a ghastly failure, they generally are now: Barrett, my old servant, who had only rejoined from hospital a short time ago, is still out there; dead, I hope for his sake, for those who are still alive and wounded must be suffering agonies from thirst and exposure.

Again both sides settled into defensive trench routines.

On 12th September, exactly six months from the inspection at Stretton, Sir Ian Hamilton visited the Munsters. Both Nightingale and Hamilton recorded the occasion. Nightingale:

It was a very different Bn to the one he saw in Egypt last. He was nice and insisted on being shown all the men and officers who had been here since the day of the landing, barely 40 in all, out of 1037.

Hamilton:

Ran across in the motor boat to see the 86th. Brigade. Went man-by-man down the lines of the four battalions — no very long walk either! Shade of Napoleon — say, which would you rather not have, a skeleton Brigade or a Brigade of skeletons’ This famous 86th Brigade is a combination. Were I a fat man, I could not bear it, but I am as insubstantial as they themselves. A life insurance office wouldn’t touch us; and yet — they kept on smiling.

As signs of winter appeared, Nightingale grew more gloomy. Then he went down with enteric fever and was evacuated to Alexandria.

In London as in Gallipoli, realisation of the hopeless futility of it all slowly dawned. Hamilton was replaced and the decision to withdraw taken. This was executed with unexpected efficiency.

Fusilier Flynn, of the 1st RMF describes the withdrawal.

When we withdrew on the 20th December it was dark. The soldiers were all packed so tight and quiet in the barges making their way to the big ships. We never lost a man, which was remarkable. As we were steaming quietly away I thought of what ‘Pincher’ Martin, who had done twenty years in the Navy, had said to me a few days after we’d arrived at Suvla Bay: “We’re not going to be flying the Union Jack here.”

He was right. We were never going to make it ours.

Almost exactly a year after arriving in Coventry, the Munsters arrived back in Egypt.

The campaign cost 114 thousand lives: 66,000 Turks; 28,000; British; 10,000 Anzacs; 10,000 French. And countless wounded.

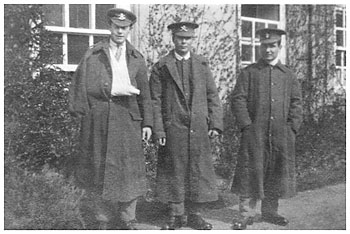

Bob and Peter Jordan? They survived. In what condition, I do not know. Certainly my father was wounded twice at Gallipoli, and there is a photograph of him in military hospital, possibly at Alexandria. He looks well enough and I guess he was lucky to get acceptable wounds. Peter was less lucky. He was severely wounded; whether at Gallipoli or later, I do not know. He was hospitalised at Clopton House, near Stratford-on-Avon for nearly a year. Mother visited him there and said that half his throat was shot away. Eventually, he was patched up and sent back to the front.

Bob and Peter Jordan? They survived. In what condition, I do not know. Certainly my father was wounded twice at Gallipoli, and there is a photograph of him in military hospital, possibly at Alexandria. He looks well enough and I guess he was lucky to get acceptable wounds. Peter was less lucky. He was severely wounded; whether at Gallipoli or later, I do not know. He was hospitalised at Clopton House, near Stratford-on-Avon for nearly a year. Mother visited him there and said that half his throat was shot away. Eventually, he was patched up and sent back to the front.

The campaign also cost Winston Churchill his job and he thought his political career was at an end. He protested loudly that his idea had not been tried properly and decided to go into the Army.

He was given command of a battalion. He thought he should have been given command of a Brigade, but got nowhere with his protests and had to cancel the brigadiers uniform he had ordered. For five months he conducted a vigorous campaign to rid his battalion of lice. Then boredom set in and his optimism and his restless ambition revived. He began to think of the possible advantages of resigning his commission and changing his party allegiance. He writes to Clementine, his wife, instructing her to mingle and use her influence in the London political scene.

Perhaps he might have a political future, after all.

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.